Akkad: "A Fascinating and Important Civilization"

Akkad was the seat of the Akkadian Empire (2334-2218 BCE), the first multi-national political entity in the world, founded by Sargon the Great (r. 2334-2279 BCE) who unified Mesopotamia under his rule and set the model for later Mesopotamian kings to follow or attempt to surpass. The Akkadian Empire set a number of "firsts' which would later become standard.

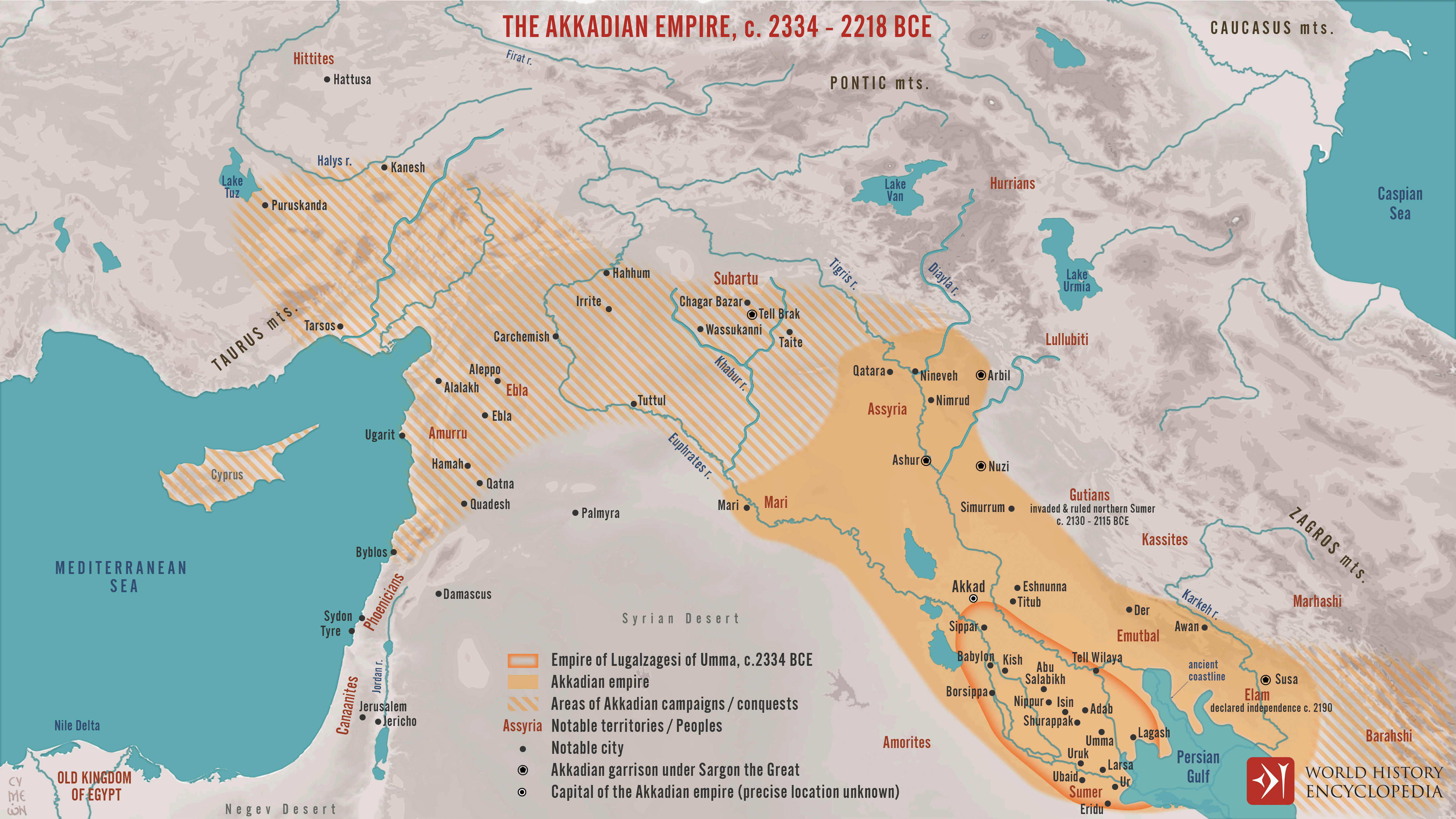

No one knows where the city of Akkad was located, how it rose to prominence, or how, precisely, it fell; yet once it was the seat of the Akkadian Empire which ruled over a vast expanse of the region of ancient Mesopotamia. It is known that Akkad (also given as Agade) was a city located along the western bank of the Euphrates River possibly between the cities of Sippar and Kish (or, perhaps, between Mari and Babylon or, even, elsewhere along the Euphrates). According to legend, it was built by the king Sargon the Great who unified Mesopotamia under the rule of his Akkadian Empire and set the standard for future forms of government in Mesopotamia.

Sargon (or his scribes) claimed that the Akkadian Empire stretched from the Persian Gulf through modern-day Kuwait, Iraq, Jordan, Syria (possibly Lebanon) through the lower part of Asia Minor to the Mediterranean Sea and Cyprus (there is also a claim it stretched as far as Crete in the Aegean). While the size and scope of the empire based in Akkad is disputed, there is no doubt that Sargon the Great created the first multinational empire in the world.

The King of Uruk & the Rise of Sargon

The language of the city, Akkadian, was already in use before the rise of the Akkadian Empire (notably in the wealthy city of Mari where vast cuneiform tablets have helped to define events for later historians), and it is possible that Sargon restored Akkad, rather than built it. It should also be noted that Sargon was not the first ruler to unite the disparate cities and tribes under one rule. The King of Uruk, Lugalzagesi, had already accomplished this, though on a much smaller scale, under his own rule.

He was defeated by Sargon who, improving on the model given him by Uruk, made his own dynasty larger and stronger.

Sargon's Rule

Sargon the Great either founded or restored the city of Akkad and ruled from 2334-2279 BCE. He conquered what he called "the four corners of the universe" and maintained order in his empire through repeated military campaigns. The stability provided by this empire gave rise to the construction of roads, improved irrigation, a wider sphere of influence in trade, as well as the abovementioned developments in arts and sciences.

The Akkadian Empire created the first postal system where clay tablets inscribed in cuneiform Akkadian script were wrapped in outer clay envelopes marked with the name and address of the recipient and the seal of the sender. These letters could not be opened except by the person they were intended for because there was no way to open the clay envelope save by breaking it.

In order to maintain his presence throughout his empire, Sargon strategically placed his best and most trusted men in positions of power in the various cities. The "Citizens of Akkad", as a later Babylonian text calls them, were the governors and administrators in over 65 different cities. Sargon also cleverly placed his daughter, Enheduanna, as High Priestess of Inanna at Ur and, through her, seems to have been able to manipulate religious/cultural affairs from afar. Enheduanna is recognized today as the world's first writer known by name and, from what is known of her life, she seems to have been a very able and powerful priestess in addition to creating her impressive hymns to Inanna.

Sargon's Successors: Rimush & Manishtusu

Sargon reigned for 56 years and after his death was succeeded by his son Rimush (r. 2279-2271 BCE) who maintained his father's policies closely. The cities rebelled after Sargon's death, and Rimush spent the early years of his reign restoring order. He campaigned against Elam, whom he defeated, and claimed in an inscription to bring great wealth back to Akkad. He ruled for only nine years before he died and was succeeded by his brother Manishtusu (r. 2271-2261 BCE). There is some speculation that Manishtusu brought about his brother's death to gain the throne.

History repeated itself after the death of Rimush, and Manishtusu had to quell widespread revolts across the empire before engaging in the business of governing his lands. He increased trade and, according to his inscriptions, engaged in long-distance trade with Magan and Meluhha (thought to be upper Egypt and the Sudan). He also undertook great projects in construction throughout the empire and is thought to have ordered the construction of the Ishtar Temple at Nineveh, which was considered a very impressive piece of architecture.

Further, he undertook land reform and, from what is known, improved upon the empire of his father and brother. Manishtusu's obelisk, describing the distribution of parcels of land, may be viewed today in the Louvre Museum, Paris.

Naram-Sin: Greatest of the Akkadian Kings

Manishtusu was succeeded by his son Naram-Sin (also Naram-Suen) who reigned from 2261-2224 BCE. Like his father and uncle before him, Naram-Sin had to suppress rebellions across the empire before he could begin to govern but, once he began, the empire flourished under his reign. In the 36 years he ruled, he expanded the boundaries of the empire, kept order within, increased trade, and personally campaigned with his army beyond the Persian Gulf and, possibly, even to Egypt.

The Victory Stele of Naram-Sin (presently housed in the Louvre) celebrates the victory of the Akkadian monarch over Satuni, king of the Lullubi (a tribe in the Zagros Mountains) and depicts Naram-Sin ascending the mountain, trampling on the bodies of his enemies, in the image of a god. Like his grandfather, he claimed himself "king of the four quarters of the universe" but, in a bolder move, began writing his name with a sign designating himself a god on equal footing with any in the Mesopotamian pantheon.

In spite of his spectacular reign, considered the height of the Akkadian Empire, later generations would associate him with The Curse of Agade, a literary text (of the Mesopotamian Naru Literature genre) ascribed to the Third Dynasty of Ur but which could have been written earlier. It tells the fascinating story of one man's attempt to wrest an answer from the gods by force, and that man is Naram-Sin. According to the text, the great Sumerian god Enlil withdrew his pleasure from the city of Akkad and, in so doing, prohibited the other gods from entering the city and blessing it any longer with their presence.

Naram-Sin does not know what he could have done to incur this displeasure and so prays, asks for signs and omens, and falls into a seven-year depression as he waits for an answer from the god. Finally, tired of waiting, he draws up his army and marches on Enlil's temple at the Ekur in the city of Nippur which he destroys. He "sets his spades against its roots, his axes against the foundations until the temple, like a dead soldier, falls prostrate" (Leick, 106).

This attack, of course, provokes the wrath not only of Enlil but of the other gods who send the Gutians "a people who know no inhibition, with human instincts but canine intelligence and with monkey features" (Leick, 106) to invade Akkad and lay it waste. There is widespread famine after the invasion of the Gutians, the dead remain rotting in the streets and houses, and the city is in ruin and so, according to the tale, ends the city of Akkad and the Akkadian Empire, a victim of one king's arrogance in the face of the gods.

There is, however, no historical record of Naram-Sin ever reducing the Ekur at Nippur by force nor destroying the temple of Enlil and it is thought that The Curse of Agade was a much later piece written to express "an ideological concern for the right relationship between the gods and the absolute monarch" (Leick, 107) whose author chose Akkad and Naram-Sin as subjects because of their, by then, legendary status. According to historical record, Naram-Sin honored the gods, had his own image placed beside theirs in the temples, and was succeeded by his son, Shar-Kali-Sharri who reigned from 2223-2198 BCE.

The Decline of Akkad

Shar-Kali-Sharri's reign was difficult from the beginning in that he, too, had to expend a great deal of effort in putting down revolts after his father's death but, unlike his predecessors, seemed to lack the ability to maintain order and was unable to prevent further attacks on the empire from without.

Interestingly, it is known that "his most important building project was the reconstruction of the Temple of Enlil at Nippur" and perhaps this event, coupled with the invasion of the Gutians and widespread famine, gave rise to the later legend which grew into The Curse of Agade. Shar-Kali-Sarri waged almost continual war against the Elamites, the Amorites, and the invading Gutians, but it is the Gutian invasion which has been most commonly credited with the collapse of the Akkadian Empire and the Mesopotamian dark age which ensued.

Recent studies, however, claim that it was most likely climate change which caused famine and, perhaps, disruption in trade, weakening the empire to the point where the type of invasions and rebellions which, in the past, were crushed, could no longer be dealt with so easily. The last two kings of Akkad following the death of Shar-Kali-Sharri, Dudu, and his son Shu-Turul, ruled only the area around the city and are rarely mentioned in association with the empire. As with the rise of the city of Akkad, its fall is a mystery and all that is known today is that, once, such a city existed whose kings ruled a vast empire, the first empire in the world, and then passed on into memory and legend.

Source: World History Encyclopedia

Publisher: Fauzi Aditya Ramadhan

Comments

Post a Comment