Skip to main content

Phoenicia: "From Tyre to Carthage: A Journey through Phoenician History"

Phoenicia

Phoenicia (),[4] or Phœnicia, was an ancient Semitic thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon.[5][6] The territory of the Phoenicians extended and shrank throughout history, with the core of their culture stretching from Arwad in modern Syria to Mount Carmel in modern Israel.[7] Beyond their homeland, the Phoenicians extended throughout the Mediterranean, from Cyprus to the Iberian Peninsula.

The Phoenicians were a Semitic-speaking people who emerged in the Levant around 3000 BC.[8] The name Phoenicia is an ancient Greek exonym that did not correspond precisely to a cohesive culture or society as it would have been understood natively.[9] It is debated whether Phoenicians were actually distinct from the broader group of Semitic-speaking peoples known as Canaanites.[10]

Historian Robert Drews believes the term "Canaanites" corresponds to

the ethnic group referred to as "Phoenicians" by the ancient Greeks;[12] archaeologist Jonathan N. Tubb argues that "Ammonites, Moabites, Israelites,

and Phoenicians undoubtedly achieved their own cultural identities, and

yet ethnically they were all Canaanites", "the same people who settled

in farming villages in the region in the 8th millennium BC."[13]: 13–14

History

Since little has survived of Phoenician records or literature, most of what is known about their origins and history comes from the accounts of other civilizations and inferences from their material culture excavated throughout the Mediterranean. The scholarly consensus is that the Phoenicians' period of greatest prominence was 1200 BC to the end of the Persian period (332 BC).[30]

The Phoenician Early Bronze Age is largely unknown.[31] The two most important sites are Byblos and Sidon-Dakerman (near Sidon), although, as of 2021, well over a hundred sites remain to be excavated, while others that have been are yet to be fully analysed.[31] The Middle Bronze Age was a generally peaceful time of increasing population, trade, and prosperity, though there was competition for natural resources.[32] In the Late Bronze Age, rivalry between Egypt, the Mittani, the Hittites, and Assyria had a significant impact on Phoenicians cities.[32]

Origins

The fourth-century BC Greek historian Herodotus claimed that the Phoenicians had migrated from the Erythraean Sea around 2750 BC and the first-century AD geographer Strabo reports a claim that they came from Tylos and Arad (Bahrain and Muharraq).[37][38][39][40] Some archaeologists working on the Persian Gulf have accepted these traditions and suggest a migration connected with the collapse of the Dilmun civilization ca. 1750 BC.[38][39][40] However, most scholars reject the idea of a migration; archaeological and historical evidence alike indicate millennia of population continuity in the region, and recent genetic research indicates that present-day Lebanese derive most of their ancestry from a Canaanite-related population.[41]

Emergence during the Late Bronze Age (1479–1200 BC)

The first known account of the Phoenicians relates to the conquests of Pharaoh Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC). The Egyptians targeted coastal cities which they wrote belonged to the Fenekhu, "carpenters", such as Byblos, Arwad, and Ullasa for their crucial geographic and commercial links with the interior (via the Nahr al-Kabir and the Orontes rivers). The cities provided Egypt with access to Mesopotamian trade and abundant stocks of the region's native cedarwood. There was no equivalent in the Egyptian homeland.[42]

By the mid-14th century BC, the Phoenician city-states were considered "favored cities" to the Egyptians. Tyre, Sidon, Beirut, and Byblos were regarded as the most important. The Phoenicians had considerable autonomy, and their cities were reasonably well developed and prosperous. Byblos was the leading city; it was a center for bronze-making and the primary terminus of precious goods such as tin and lapis lazuli from as far east as Afghanistan. Sidon and Tyre also commanded interest among Egyptian officials, beginning a pattern of rivalry that would span the next millennium.

The Amarna letters report that from 1350 to 1300 BC, neighboring Amorites and Hittites were capturing Phoenician cities, especially in the north. Egypt subsequently lost its coastal holdings from Ugarit in northern Syria to Byblos near central Lebanon.

Ascendance and high point (1200–800 BC)

Sometime between 1200 and 1150 BC, the Late Bronze Age collapse severely weakened or destroyed most civilizations in the region, including the Egyptians and Hittites. The Phoenicians appear to have weathered the crisis relatively well, emerging as a distinct and organized civilization in 1230 BC. The period is sometimes described as a "Phoenician renaissance."[43] They filled the power vacuum caused by the Late Bronze Age collapse by becoming the sole mercantile and maritime power in the region, a status they would maintain for the next several centuries.[10]

The recovery of the Mediterranean economy can be credited to Phoenician mariners and merchants, who re-established long-distance trade between Egypt and Mesopotamia in the 10th century BC.[44]

Early into the Iron Age, the Phoenicians established ports, warehouses, markets, and settlement all across the Mediterranean and up to the southern Black Sea. Colonies were established on Cyprus, Sardinia, the Balearic Islands, Sicily, and Malta, as well as the coasts of North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula.[45] Phoenician hacksilver dated to this period bears lead isotope ratios matching ores in Sardinia and Spain, indicating the extent of Phoenician trade networks.[46]

By the tenth century BC, Tyre rose to become the richest and most powerful Phoenician city-state, particularly during the reign of Hiram I (c. 969–936 BC). During the rule of the priest Ithobaal (887–856 BC), Tyre expanded its territory as far north as Beirut and into part of Cyprus; this unusual act of aggression was the closest the Phoenicians ever came to forming a unitary territorial state. Once his realm reached its largest territorial extent, Ithobaal declared himself "King of the Sidonians," a title that would be used by his successors and mentioned in both Greek and Jewish accounts.[47]

The Late Iron Age saw the height of Phoenician shipping, mercantile, and cultural activity, particularly between 750 and 650 BC. The Phoenician influence was visible in the "orientalization" of Greek cultural and artistic conventions.[10] Among their most popular goods were fine textiles, typically dyed with Tyrian purple. Homer's Iliad, which was composed during this period, references the quality of Phoenician clothing and metal goods.[10]

Foundation of Carthage

Carthage was founded by Phoenicians coming from Tyre, probably initially as a station in the metal trade with the southern Iberian Peninsula.[48][page needed] The city's name in Punic, Qart-Ḥadašt (𐤒𐤓𐤕 𐤇𐤃𐤔𐤕), means "New City".[49] There is a tradition in some ancient sources, such as Philistos of Syracuse, for an "early" foundation date of around 1215 BC—before the fall of Troy in 1180 BC. However, Timaeus, a Greek historian from Sicily c. 300 BC, places the foundation of Carthage in 814 BC, which is the date generally accepted by modern historians.[50] Legend, including Virgil's Aeneid, assigns the founding of the city to Queen Dido. Carthage would grow into a multi-ethnic empire spanning North Africa, Sardinia, Sicily, Malta, the Balearic Islands, and southern Iberia, but would ultimately be destroyed by Rome in the Punic Wars (264–146 BC) before being rebuilt as a Roman city.[citation needed]

Vassalage under the Assyrians and Babylonians (858–538 BC)

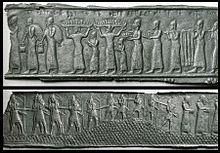

Main articles: Phoenicia under Assyrian rule and Phoenicia under Babylonian rule Two bronze fragments from an Assyrian palace gate depicting the collection of tribute from the Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon (859–824 BC). British Museum.

Main articles: Phoenicia under Assyrian rule and Phoenicia under Babylonian rule Two bronze fragments from an Assyrian palace gate depicting the collection of tribute from the Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon (859–824 BC). British Museum.

As a mercantile power concentrated along a narrow coastal strip of land, the Phoenicians lacked the size and population to support a large military. Thus, as neighboring empires began to rise, the Phoenicians increasingly fell under the sway of foreign rulers, who to varying degrees circumscribed their autonomy.[47]

The Assyrian conquest of Phoenicia began with King Shalmaneser III. He rose to power in 858 BC and began a series of campaigns against neighboring states. The Phoenician city-states fell under his rule, forced to pay heavy tribute in money, goods, and natural resources. Initially, they were not annexed outright—they remained in a state of vassalage, subordinate to the Assyrians but allowed a certain degree of freedom.[47] This changed in 744 BC with the ascension of Tiglath-Pileser III. By 738 BC, most of the Levant, including northern Phoenicia, were annexed; only Tyre and Byblos, the most powerful city-states, remained tributary states outside of direct Assyrian control.

Tyre, Byblos, and Sidon all rebelled against Assyrian rule. In 721 BC, Sargon II besieged Tyre and crushed the rebellion. His successor Sennacherib suppressed further rebellions across the region. During the seventh century BC, Sidon rebelled and was destroyed by Esarhaddon, who enslaved its inhabitants and built a new city on its ruins. By the end of the century, the Assyrians had been weakened by successive revolts, which led to their destruction by the Median Empire.

The Babylonians, formerly vassals of the Assyrians, took advantage of the empire's collapse and rebelled, quickly establishing the Neo-Babylonian Empire in its place. Phoenician cities revolted several times throughout the reigns of the first Babylonian King, Nabopolassar (626–605 BC), and his son Nebuchadnezzar II (c. 605–c. 562 BC). In 587 BC Nebuchadnezzar besieged Tyre, which resisted for thirteen years, but ultimately capitulated under "favorable terms".[51]

Persian period (539–332 BC)

In 539 BC, Cyrus the Great, king and founder of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, took Babylon.[52] As Cyrus began consolidating territories across the Near East, the Phoenicians apparently made the pragmatic calculation of "[yielding] themselves to the Persians."[53] Most of the Levant was consolidated by Cyrus into a single satrapy (province) and forced to pay a yearly tribute of 350 talents, which was roughly half the tribute that was required of Egypt and Libya.[54]

The Phoenician area was later divided into four vassal kingdoms—Sidon, Tyre, Arwad, and Byblos—which were allowed considerable autonomy. Unlike in other empire areas, there is no record of Persian administrators governing the Phoenician city-states. Local Phoenician kings were allowed to remain in power and given the same rights as Persian satraps (governors), such as hereditary offices and minting their coins.[52][55] Achaemenid-era coin of Abdashtart I of Sidon, who is seen at the back of the chariot, behind the Persian King.

The Phoenicians remained a core asset to the Achaemenid Empire, particularly for their prowess in maritime technology and navigation;[52] they furnished the bulk of the Persian fleet during the Greco-Persian Wars of the late fifth century BC.[56] Phoenicians under Xerxes I built the Xerxes Canal and the pontoon bridges that allowed his forces to cross into mainland Greece.[57] Nevertheless, they were harshly punished by the Persian King following his defeat at the Battle of Salamis, which he blamed on Phoenician cowardice and incompetence.[58]

In the mid-fourth century BC, King Tennes of Sidon led a failed rebellion against Artaxerxes III, enlisting the help of the Egyptians, who were subsequently drawn into a war with the Persians.[59] The resulting destruction of Sidon led to the resurgence of Tyre, which remained the dominant Phoenician city for two decades until the arrival of Alexander the Great.

Hellenistic period (332–152 BC)

Phoenicia was one of the first areas to be conquered by Alexander the Great during his military campaigns across western Asia. Alexander's main target in the Persian Levant was Tyre, now the region's largest and most important city. It capitulated after a roughly seven month siege, during which many of its citizens fled to Carthage.[60] Tyre's refusal to allow Alexander to visit its temple to Melqart, culminating in the killing of his envoys, led to a brutal reprisal: 2,000 of its leading citizens were crucified and a puppet ruler was installed.[61] The rest of Phoenicia easily came under his control, with Sidon surrendering peacefully.[62] A naval action during Alexander the Great's Siege of Tyre (332 BC). Drawing by André Castaigne, 1888–89.

Alexander's empire had a Hellenization policy, whereby Hellenic culture, religion, and sometimes language were spread or imposed across conquered peoples. However, Hellenisation was not enforced most of the time and was just a language of administration until his death. This was typically implemented through the founding of new cities, the settlement of a Macedonian or Greek urban elite, and the alteration of native place names to Greek.[60] However, there was no organized Hellenization in Phoenicia, and with one or two minor exceptions, all Phoenician city-states retained their native names, while Greek settlement and administration appear to have been very limited.[60]

The Phoenicians maintained cultural and commercial links with their western counterparts. Polybius recounts how the Seleucid King Demetrius I escaped from Rome by boarding a Carthaginian ship that was delivering goods to Tyre.[60] The adaptation to Macedonian rule was likely aided by the Phoenicians' historical ties with the Greeks, with whom they shared some mythological stories and figures; the two peoples were even sometimes considered "relatives."[60]

When Alexander's empire collapsed after his death in 323 BC, the Phoenicians came under the control of the largest of its successors, the Seleucids. The Phoenician homeland was repeatedly contested by the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt during the forty-year Syrian Wars, coming under Ptolemaic rule in the third century BC.[51] The Seleucids reclaimed the area the following century, holding it until the mid-first 2nd century BC. Under their rule, the Phoenicians were allowed a considerable degree of autonomy and self-governance.[51]

During the Seleucid Dynastic Wars (157–63 BC), the Phoenician cities were mainly self-governed. Many of them were fought for or over by the warring factions of the Seleucid royal family. Some Phoenician regions were under the control and influence of the Jews, who revolted and succeeded in defeating Seleucids in 164 BC.

The Seleucid Kingdom, including Phoenicia, was seized by Tigranes the Great of Armenia in 82 BC, ending the Hellenistic influence on the region.

With their strategically valuable buffer state absorbed into a rival power, the Romans intervened and conquered the territory in 62 BC. Shortly after that, the territory was incorporated into the Roman province of Syria. Phoenicia became a separate province in the third century AD. With the Roman invasion, whatever political autonomy Phoenicians had was dissolved, and the region was romanized. The Roman Empire ruled the province up to the 640s when the Muslim Arabs invaded the region successfully, and a process of Islamisation and Arabisation started.

Publisher : Rakha Ahnafa

Comments

Post a Comment