Inca Civilization: "From Cuzco to Machu Picchu"

Inca Civilization

The Inca Civilization flourished in ancient Peru between c. 1400 and 1533 CE. The Inca Empire eventually extended across western South America from Quito in the north to Santiago in the south. It was the largest empire ever seen in the Americas and the largest in the world at that time.

Undaunted by the often harsh Andean environment, the Incas conquered people and exploited landscapes in such diverse settings as plains, mountains, deserts, and tropical jungles. Famed for their unique art and architecture, they constructed finely built and imposing buildings wherever they conquered, and their spectacular adaptation of natural landscapes with terracing, highways, and mountaintop settlements continues to impress modern visitors at such world-famous sites as Machu Picchu.

Historical Overview

As with other ancient American cultures, the historical origins of the Incas are difficult to disentangle from the founding myths they created. According to legend, in the beginning, the creator god Viracocha came out of the Pacific Ocean, and when he arrived at Lake Titicaca, he created the sun and all ethnic groups. These first people were buried by the god and only later did they emerge from springs and rocks (sacred ocarinas) back into the world. The Incas, specifically, were brought into existence at Tiwanaku (Tiahuanaco) from the sun god Inti; hence, they regarded themselves as the chosen few, the 'Children of the Sun', and the Inca ruler was Inti's representative and embodiment on earth. In another version of the creation myth, the first Incas came from a sacred cave known as Tampu T'oqo or 'The House of Windows', which was located at Pacariqtambo, the 'Inn of Dawn', south of Cuzco. The first pair of humans was Manco Capac (or Manqo Qhapaq) and his sister (also his wife) Mama Oqllu (or Ocllo). Three more brother-sister siblings were born, and the group set off together to find their civilization. Defeating the Chanca people with the help of stone warriors (pururaucas), the first Incas finally settled in the Valley of Cuzco and Manco Capac, throwing a golden rod into the ground, established what would become the Inca capital, Cuzco.

More concrete archaeological evidence has revealed that the first settlements in the Cuzco Valley actually date to 4500 BCE when hunter-gatherer communities occupied the area. However, Cuzco only became a significant centre sometime at the beginning of the Late Intermediate Period (1000-1400 CE). A process of regional unification began in the late 14th century CE, and from the early 15th century CE, with the arrival of the first great Inca leader Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui ('Reverser of the World') and the defeat of the Chanca in 1438 CE, the Incas began to expand in search of plunder and production resources, first to the south and then in all directions. They eventually built an empire which stretched across the Andes, conquering such peoples as the Lupaka, Colla, Chimor, and Wanka civilizations along the way. Once established, a nationwide system of tax and administration was instigated which consolidated the power of Cuzco.

Inca Government & Administration

The Incas kept lists of their kings (Sapa Inca) so that we know of such names as Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui (reign c. 1438-63 CE), Thupa Inca Yupanqui (reign c. 1471-93 CE), and Wayna Qhapaq (the last pre-Hispanic ruler, reign c. 1493-1525 CE). It is possible that two kings ruled at the same time and that queens may have had some significant powers, but the Spanish records are not clear on both points. The Sapa Inca was an absolute ruler, and he lived a life of great opulence. Drinking from gold and silver cups, wearing silver shoes, and living in a palace furnished with the finest textiles, he was pampered to the extreme. He was even looked after following his death, as the Inca mummified their rulers. Stored in the Coricancha temple in Cuzco, the mummies (marquis) were, in elaborate ceremonies, regularly brought outside wearing their finest regalia, given offerings of food and drink, and 'consulted' for their opinion on pressing state affairs.

Inca rule was, much like their architecture, based on compartmentalised and interlocking units. At the top was the ruler and ten kindred groups of nobles called panaqa. Next in line came ten more kindred groups, more distantly related to the king and then, a third group of nobles not of Inca blood but made Incas as a privilege. At the bottom of the state apparatus were locally recruited administrators who oversaw settlements and the smallest Andean population unit the ayllu, which was a collection of households, typically of related families who worked an area of land, lived together and provided mutual support in times of need. Each ayllu was governed by a small number of nobles or kurakas, a role which could include women.

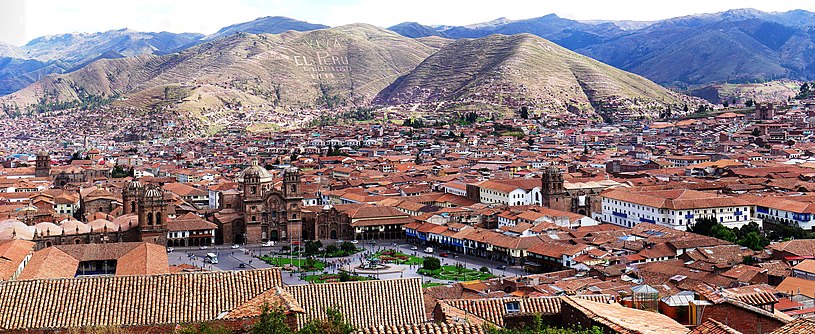

Cuzco

The Inca capital of Cuzco (from Qosqo, meaning 'dried-up lake bed' or perhaps derived from Cuzco, a particular stone marker in the city) was the religious and administrative centre of the empire and had a population of up to 150,000 at its peak. Dominated by the sacred gold-covered and emerald-studded Coricancha complex (or Temple of the Sun), its greatest buildings were credited to Pachacuti. Most splendid were the temples built in honour of Inti and Mama Kilya - the former was lined with 700 2 kg sheets of beaten gold, the latter with silver. The whole capital was laid out in the form of a puma (although some scholars dispute this and take the description metaphorically) with the imperial metropolis of Pumachupan forming the tail and the temple complex of Sacsayhuaman (or Saqsawaman) forming the head. Incorporating vast plazas, parklands, shrines, fountains, and canals, the splendour of Inca Cuzco now, unfortunately, survives only in the eyewitness accounts of the first Europeans who marvelled at its architecture and riches.

Inca Religion

The Inca had great reverence for two earlier civilizations who had occupied much the same territory - the Wari and Tiwanaku. As we have seen, the sites of Tiwanaku and Lake Titicaca played an important part in Inca creation myths and so were especially revered. Inca rulers made regular pilgrimages to Tiwanaku and the islands of the lake, where two shrines were built to Inti the Sun god and supreme Inca deity, and the moon goddess Mama Kilya. Also in the Coricancha complex at Cuzco, these deities were represented by large precious metal artworks which were attended and worshipped by priests and priestesses led by the second most important person after the king: the High Priest of the Sun (Willaq Umu). Thus, the religion of the Inca was preoccupied with controlling the natural world and avoiding such disasters as earthquakes, floods, and droughts, which inevitably brought about the natural cycle of change, the turning over of time involving death and renewal which the Inca called pachakuti.

Sacred sites were also established, often taking advantage of prominent natural features such as mountain tops, caves, and springs. These huacas could be used to take astronomical observations at specific times of the year. Religious ceremonies took place according to the astronomical calendar, especially the movements of the sun, moon, and Milky Way (Mayu). Processions and ceremonies could also be connected to agriculture, especially the planting and harvesting seasons. Along with Titicaca's Island of the Sun, the most sacred Inca site was Pachacamac, a temple city built in honour of the god with the same name, who created humans, and plants, and was responsible for earthquakes. A large wooden statue of the god considered an oracle, brought pilgrims from across the Andes to worship at Pachacamac. Shamans were another important part of the Inca religion and were active in every settlement. Cuzco had 475, the most important being the yacarca, the personal advisor to the ruler.

Inca Architecture & Roads

Master stonemasons, the Incas constructed large buildings, walls and fortifications using finely worked blocks - either regular or polygonal - which fitted together so precisely no mortar was needed. With an emphasis on clean lines, trapezoid shapes, and incorporating natural features into these buildings, they have easily withstood the powerful earthquakes which frequently hit the region. The distinctive sloping trapezoid form and fine masonry of Inca buildings were, besides their obvious aesthetic value, also used as a recognisable symbol of Inca domination throughout the empire.

One of the most common Inca buildings was the ubiquitous one-room storage warehouse the Jolla. Built-in stone and well-ventilated, they were either round and stored maize or square for potatoes and tubers. The kallanka was a very large hall used for community gatherings. More modest buildings include the kancha - a group of small single-room and rectangular buildings (wasi and masma) with thatched roofs built around a courtyard enclosed by a high wall. The kancha was a typical architectural feature of Inca towns, and the idea was exported to conquered regions. Terracing to maximise land area for agriculture (especially for maize) was another Inca practice, which they exported wherever they went. These terraces often included canals, as the Incas were experts at diverting water, carrying it across great distances, channelling it underground, and creating spectacular outlets and fountains.

Inca Art

Although influenced by the art and techniques of the Chimu civilization, the Incas did create their own distinctive style which was an instantly recognisable symbol of imperial dominance across the empire. Inca art is best seen in highly polished metalwork (in gold - considered the sweat of the sun, silver - considered the tears of the moon, and copper), ceramics, and textiles, with the last being considered the most prestigious by the Incas themselves. Designs often use geometrical shapes, are technically accomplished, and standardized. The checkerboard stands out as a very popular design. One of the reasons for repeated designs was that pottery and textiles were often produced for the state as a tax, and so artworks were representative of specific communities and their cultural heritage. Just as today's coins and stamps reflect a nation's history, so, too, Andean artwork offered recognisable motifs which either represented the specific communities making them or the imposed designs of the ruling Inca class ordering them.

Works using precious metals such as discs, jewellery, figures, and everyday objects were made exclusively for Inca nobles, and even some textiles were restricted for their use alone. Goods made using the super-soft vicuña wool were similarly restricted, and only the Inca ruler could own vicuña herds. Ceramics were for wider use, and the most common shape was the urpu, a bulbous vessel with a long neck and two small handles low on the pot which was used for storing maize. Notably, the pottery decoration, textiles, and architectural sculpture of the Incas did not usually include representations of themselves, their rituals, or such common Andean images as monsters and half-human, half-animal figures.

Publisher: M. Celio Durrani

Source: World History Encyclopedia

Comments

Post a Comment